“You can't base your life on other people's expectations.” Stevie Wonder

Ever since the revolution of the 70s and 80s, rational expectations, popularised by Robert Lucas in 1972 have played a fundamental role in macroeconomic theory. Before this, it was assumed that agents' expectations were adaptive. Essentially, they were backward-looking to the extent that their expectations of any variable were merely last period’s actual reading.

Lucas and the revolutionists, however, suggested that people were much cleverer than this. In particular, he declared agents forward-looking, with their expectations of the future developed by taking into account past and present events in the correct way, naming 'them 'rational'. The beauty stems from it (broadly) making intuitive sense. Simply, if you think that the price of a car will be 10% higher tomorrow, you're likely to buy it today instead. That is, your actions today reflect your expectations of what will happen in the future.

Formalising rationalising expectations

The use of math in economic theory is both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side, it means that there’s no room for ambiguity - there’s no ‘I said x, but what I meant to say was y’ argument to be had, because math requires precise definitions of every variable. But the problem is that sometimes you have to define things that are really hard to define. One of these is rational expectations.

So how were they defined? For a long time, rational expectations assumed agents to have perfect foresight - their expectations of inflation in a model were exactly what inflation came out to be. While this might seem ridiculous at face value, slightly deeper reflection leads you to the idea that rational expectations means that, at least in the long run, expectations of, say inflation, coincide with actual inflation outcomes. This, on the other hand, does not seem as strong an assumption.

Even so, how does this theory stack up against the evidence? Is it another one of those implausible assumptions that the economics profession makes? In the remainder of this post, I pit the theory against the data using three basic tests of rationality

The data comes from the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) for the euro area - a quarterly survey of expectations for some of the euro area’s key macroeconomic variables. Importantly, the panel consists of around 90 financial sector and non-financial sector forecasters from a range of different countries within the EU. The choice of this survey compared to other surveys ties into the belief that rationality itself is quite hard to achieve. As such, if anyone can satisfying the theory, people who are paid to forecast for a living should have the best chance of doing so. The tests and analysis I conduct stems from Mankiw and Reis (2004), who conduct a more elaborate version of this study using US data and surveys from multiple sources.

The Data

These tests of rationality are conducted using the data of HICP inflation expectations (source: SPF) and actual in the euro area from1999 to Q4 2015 (source: Eurostat).

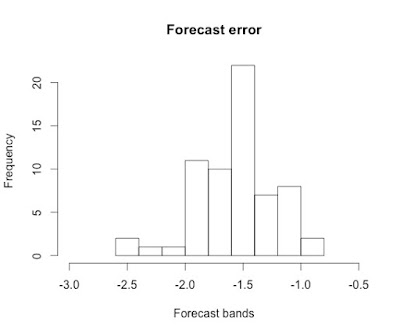

First a word on the data: looking at the period as a whole, forecasts seem to have been always too optimistic. As you can see from the histogram above, forecast errors (defined as actual inflation minus expected) take readings from -0.9 to -2.5, entered around -1.5. This seems to be quite stable, as splitting the period up into pre- and post-crisis doesn’t yield significantly different distributions. Indeed, the data suggest that forecasters have always been disappointed when it comes to inflation in the euro area.

1) Bias

The first test of rationality checks whether, on average, forecast errors are unbiased. That is, forecasters should not have preconceived notions on how inflation will turn out that affects their forecasts. In a deeper sense, the theory claims that they take into account previous data that leads their expectations to be, on average, correct. In terms of the data, this would be represented by a regression of the forecast error against a constant. Given we would expect rational agents to be unbiased, we would expect the coefficient on the constant to be 0.

We can see the results of this regression in column 1 of Table 1 below. The coefficient is negative and significantly different from zero at the 1% level. Therefore, the data suggest that economist forecasts are not unbiased, and specifically biased upwards. It’s worth noting that result still holds when we split the data up in to pre- and post-crisis periods.

Conclusion: Test 1 refutes the rational expectations theory claim.

2) Persistence

Here we check whether forecast errors are correlated with those in the past (specifically, those four quarters ago - in line with Mankiw and Reis (2004)). Rational expectations theory tells us that if agents notice that their errors were, say, too low in a previous forecast, they should internalise their error and correct for it in the future. Empirically, we look at a regression of errors against its own lag. This would take the form of the coefficient on the lagged term equal to zero if the rational expectations hypothesis were to hold.

As we can see in the second column of the table, the coefficient is not different from zero, even at the 10% significance level. But note that the coefficient is significantly different from zero when we look at the pre-crisis period (not shown here). Though we choose to discount this given this particular regression has only few (33) data points, it is still noteworthy.

Conclusion: Test 2 confirms the rational expectations theory claim.

3) Forecast revisions

One can only form expectations given the current information set available. But as new data come in, rational expectations would require that the new data is fully incorporated into the new forecast. As such, for rational expectations to hold, it must be that the change in the forecast (revisions) should not tell us anything about the forecast error in period t. As such, a regression of the forecast error on forecast revisions should gives us a slope coefficient of 0.

This is shown in column 3 of the table. The slope coefficient on revisions is not significantly different from 0 (even at the 10% level), implying that these forecasters do fully (in the statistical sense) incorporate new information into their revised forecasts. It is, again, worth noting that this result holds in both the pre- and post-crisis periods.

Conclusion: Test 3 confirms the rational expectations theory claim.

Table 1

| Forecast error | Forecast error | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Constant | -1.52*** | -1.08*** | -1.53*** |

| (0.08) | (0.32) | (0.06) | |

| Forecast error lag (t-4) | 0.30 | ||

| (0.22) | |||

| Forecast revisions (t-1) | 0.48 | ||

| (0.32) | |||

| Observations | 64 | 61 | 61 |

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Notes: | ***Significant at the 1 percent level. | ||

| **Significant at the 5 percent level. | |||

| *Significant at the 10 percent level. | |||

| Standard errors in parentheses; Newey-West standard errors to correct for serially correlated errors, lag = 4 | |||

The bottom line

Rational expectations have been one of the most influential concepts in macroeconomics, playing a part in almost all mainstream economic theory since the mid-70s. Moreover, it’s feature of forward-looking individuals has given rise to unconventional policy proposals such as quantitative easing and forward guidance, that arguably prevented the world economy from falling into another Great Depression. But how realistic is it? Through a euro area inflation expectations lens, the data suggest that EU inflation forecasters exhibit something close to expectations that are rational. Mankiw and Reis (2004) also find something that broadly resembles rationality when using the US SPF. Indeed, and somewhat contrary to popular opinion, the rational expectations tenet is not something far from reality.

Stevie Wonder once said ‘you can't base your life on other people’s expectations’. While that may be good life advice, let’s just hope, for the sake of our economic models, that you at least base your life on your own!

No comments:

Post a Comment